Autumn 1941 The battalion commander posed an impossible task for a detachment of six: to detain German troops for a day at an unnamed railway crossing. The commander assigned the command of the detachment to Sergeant Karpenko. As soon as the short column of the battalion was out of sight, the foreman distributed positions between the soldiers. Pshenichny got the flanking position, Fisher began to dig behind him, followed by Ovseev, Whistle and Glechik. By evening, everyone had equipped their positions except Fisher. Petty Officer remembered that they still did not have a sentinel, and decided that the most suitable candidate for this post was an unskilled scientist.

Wheat dug his trench still before dawn. Having retired, he decided to have a bite to eat and took out the lard hidden from his comrades. Distant machine gun bursts interrupted his lunch. The soldiers were alarmed, especially when Ovseev said that they were being surrounded, and the entire detachment consisted of suicide bombers. The foreman quickly stopped this conversation, but Pshenichny had already decided to surrender.

The life of Ivan Pshenichny developed "awkwardly and bitterly." His father was a wealthy peasant, a fist. Harsh and tough, he "ruthlessly schooled his son in simple agricultural science." Pshenichny began to hate his father by making friends with a farm laborer, a distant maternal relative. This friendship continued even after a few years, when the former farm laborer, having served in the army, became "the ringleader of all youth affairs in the village." Once, Ivan attended a rehearsal of the "atheist" play, which was staged by village youth. Wheat-father did not like this, and he threatened to drive the atheist out of the house. Ivan could not break with his family. A few years later, the Pshenichnys were dispossessed and sent to Siberia. Ivan himself avoided this - he studied at the age of seven and lived with his uncle. However, the past did not release Pshenichny. He worked diligently, but wherever his fate brought, his “non-proletarian” origin surfaced. Gradually, Ivan became hardened, learned the worldly rule: "only by itself, for itself, despite everything." He was probably gloating alone when the war broke out.

In the evening it began to rain. The foreman decided to connect the dug-out shelters with a moat. The trench was only ready by midnight. The whistle shut the window and melted the stove in the surviving station gatehouse. Soon, the rest of the fighters took refuge in it. Gathering "peace of mind", Whistle made dinner, managing to steal from Pshenichny an unfinished piece of fat. The foreman knew that the Whistle had once been in a colony, and he directly asked about it.

Exhausted by hearty food, Whistle told his story. Vitka Whistle was born in Saratov. His mother worked at a bearing factory, and Vitka, who had grown up, also went to work there. However, the monotonous work did not please Whistler. From hopelessness, the guy began to drink. So I met a man who offered him a new job - a seller in a bakery. Through Vitka this man began to sell “left” bread. Vitka got extra money, and then he fell in love. Girl Whistle "belonged" to the leader of the gang. He ordered Vitka to bypass her. A fight ensued. Once in the police, Whistle heard the leader called by a stranger, got angry and handed over the gang to the investigator. In Siberia, at logging, Vitka spent two years. After an amnesty, he went to the Far East and became a sailor on a fishing vessel. When the war began, Vitka did not want to sit out in the rear. The head of the NKVD helped - he identified Whistle in the infantry division. The Whistle did not consider himself innocent, he only wanted that his past not be remembered.

Ovseeva foreman appointed guard. Standing in the cold rain, he thought about tomorrow. Ovseev did not want to die. He considered himself an extremely talented person. "In the company, Ovseev lived on his own." He considered himself much smarter and more intelligent than others. He despised some, did not pay attention to others, but no one was equal to Ovseev himself, and they exacted him from him as well as from others. It seemed extremely unfair to him.

Alik Ovseev realized his exceptionalism at school, which his mother contributed a lot to. Alik’s father, a third-level military doctor, practically didn’t raise his son, “but his mother, already a middle-aged and very kind woman,” adored her brilliant son. Having tried all forms of art, from painting to music, Alik realized: “fanatical dedication, perseverance and hard labor are needed there.” This was not suitable for Ovseev - he wanted to achieve more with small means. Alik’s sports career didn’t work either. He was expelled from the football team for being rude. Then Ovseev chose a military career and became a cadet of the school. He dreamed of exploits and glory, and was greatly disappointed. The commanders stubbornly did not notice his exclusivity, and the rest of the cadets disliked him. Soon after the outbreak of the war, Ovseev realized that war was not a feat, but blood, dirt and death. He decided that "this is not for him," and since then has sought only one thing - to survive. Today, luck has completely changed him. Ovseev did not find a way out of this trap.

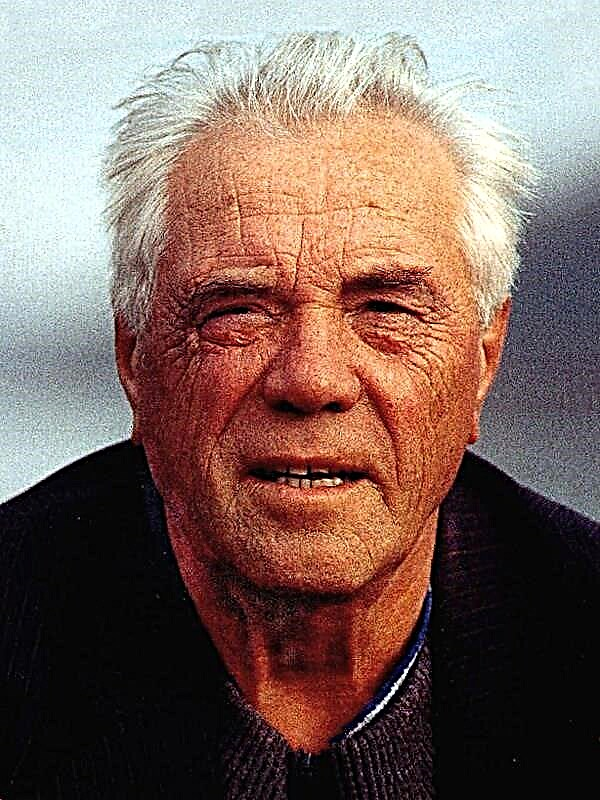

After Ovseev, Glechik fell on duty. This was the youngest of six fighters. During the war, Glechik “became rather coarse in his soul and ceased to notice the minor adversities of life”. In his mind lived "only one all-consuming pain." Vasily Glechik was born in a small Belarusian village and grew up as a “timid and silent boy.” Vasya's father worked as a killer at a local brick factory. His mother was calm, cheerful and cheerful. "When the mother was offended, Cornflower could not feel happy." Glechik’s happy life ended when his father died - Glechik Sr. was killed by electric shock. “Life has become difficult, painfully boring and lonely,” because the mother had to raise two children alone - Vasilka and his sister Nastochka. After the end of the seven-year period, mother sent Vasilka to study further, and she got a job at a brick factory to form a tile. Gradually, she calmed down, and then noticeably cheered. One fine day, the mother brought home a middle-aged man, a factory accountant, and said that he would become their father. Glechik ran away from home and enrolled in the Vitebsk school of FZO. His mother found him, begged him to return, but Vasya did not answer letters. When the war broke out, the stepfather went to the front, his mother and sister were left alone again, and Vasya doubted. While he was thinking, the Germans approached Vitebsk, and Glechik had to escape. Having reached Smolensk, he joined the army as a volunteer. Now he was tormented by only one grief: he offended his mother, left her alone.

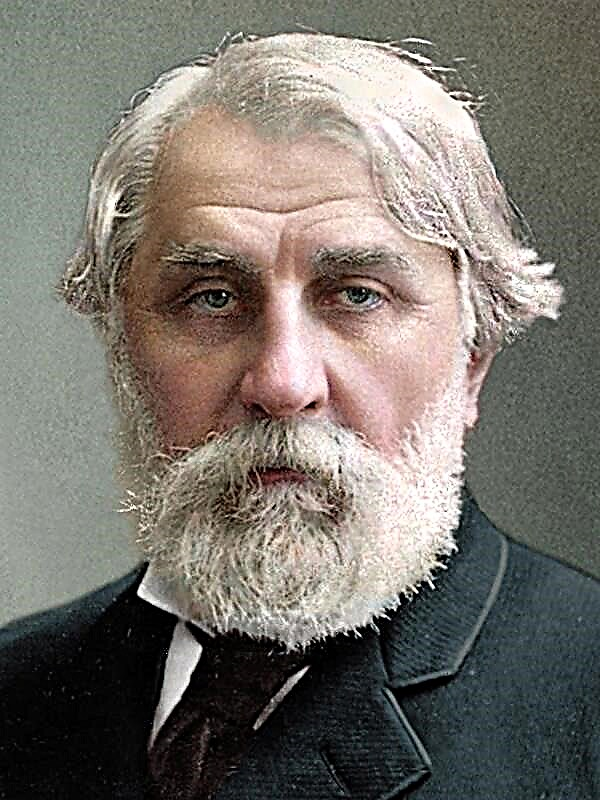

In the station gatehouse, meanwhile, everyone was asleep. Grigory Karpenko also fell asleep. In a dream, he saw his father and three brothers. The foreman's father was a peasant. He did not want to divide his small land allotment into three parts, he gave the entire estate to his eldest son. Karpenko was the youngest. After ten years of military service, he fell into the Finnish War, where he received the medal "For Military Merit." After being transferred to the reserve, Karpenko was “appointed deputy director of the flax mill,” and Karpenko “married Katya, a young teacher at a local elementary school.” Together with the director, the “one-armed red partisan,” they made their factory the best in the area. When the war began, Karpenko’s wife was expecting a baby. At the front, Gregory was lucky; he was used to feeling his invulnerability. Luck changed Karpenko only today, but was not going to retreat. The stocky, well-knocked foreman had one firm rule of life: “hide everything dubious, indefinite, and expose only confidence and unshakable firmness of will”.

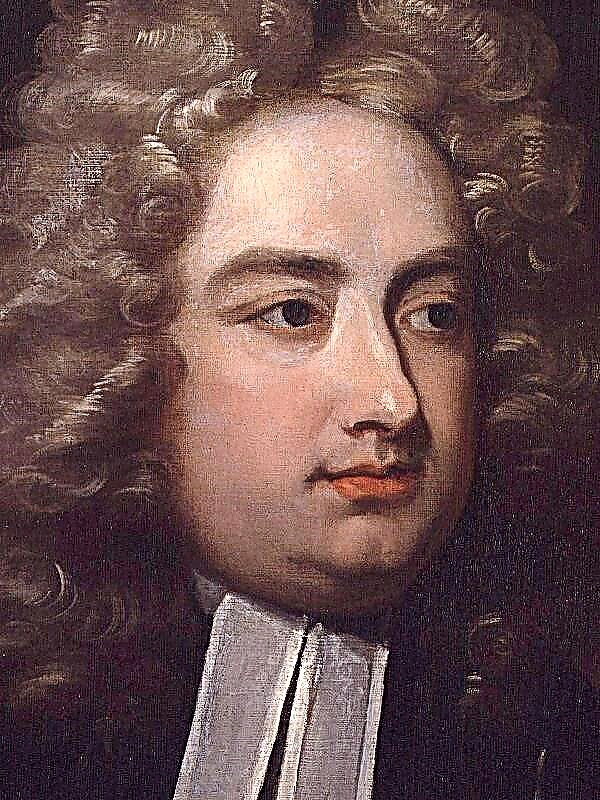

The beginning of dawn. The "forward looking" Fisher had long dug up a refuge for himself and was now thinking about the foreman. He evoked in Fisher a "complex and contradictory feeling." The scientist was oppressed by his exactingness, callousness and evil shouts. But as soon as he became not a foreman, but just a comrade, Fisher was ready to carry out any of his orders. Fisher could not understand how he, a young and capable scientist, secretly "tried to please some kind of illiterate soldaphone." Boris Fisher considered himself not too young - "recently exchanged the fourth dozen."

He was born in Leningrad. Father introduced the art of Boris. Finally, taking up the brush, Fisher realized that a great artist would not work out of him, but the art did not leave his life. At 25, Boris became a candidate of science in the field of art history. In the army, he became a "black sheep". Fisher felt how “a rude front-line life daily and inexorably erased in his soul the great value of art, which was increasingly inferior to the cruel laws of struggle.” Fisher began to doubt: whether he was mistaken, giving art the best years of his life.

After Ovseev, Pshenichny stood on the clock. Coming out of the gatehouse, he felt that the next stage of his life had ended. Now the most reasonable, in his opinion, "will surrender to the Germans - at their mercy and power." He hoped that the Germans would appoint him to some advantageous position. With these thoughts, Pshenichny reached the nearest village. The Germans jumped out from the nearest hut. In vain did Pshenichny explain to them that he was "captive." The Germans told him to follow the road, and then they shot him in cold blood.

This machine gun burst woke Fisher. He scaredly jumped up in the trench and heard the distant crack of motorcycle engines. Fisher felt that "a minute is coming that will finally show what his life was worth." When the first motorcycles appeared out of the fog, Fisher "realized that he had little chance of getting there." Fisher shot the whole cartridge without causing any damage to the enemies. Finally, he calmed down, carefully aimed, and managed to seriously injure a German officer sitting in a motorcycle stroller. This was the only feat of the scientist. The Germans approached the trench and shot him point blank.

The sounds of gunfire raised the rest of the fighters. Only now the foreman discovered that Pshenichny disappeared, and after a while realized that he had lost another fighter. They repulsed the first wave of motorcycles and transporters. The whole small detachment was filled with enthusiasm. Ovseev especially boasted, although he spent most of the battle cowering at the bottom of the trench. He already realized that Pshenichny had escaped, and now regretted that he had not followed his example. The whistle was still not discouraged. He made a sortie to the crashed transporter, where he got a brand new machine gun and ammunition for it. Generous, Whistle gave the foreman a golden watch pulled from the pocket of the murdered German, and when Karpenko smashed it against the wall of the gatehouse, he only scratched the back of his head.

The foreman handed over the delivered machine gun to Ovseev, who was not too happy. Ovseev perfectly understood that it was the machine gunners who died first. In the next attack, the Germans threw tanks. The very first shot of a tank gun damaged the only PTR detachment and seriously wounded the foreman. The whistle died, rushing under a tank with an armor-piercing grenade. The tanks moved back, and Glechik looked up from the rifle. The foreman was unconscious. "The worst thing for Glechik was to witness the death of their always decisive, imperious foreman." Ovseev, meanwhile, decided that it was time to get away. He jumped out of the trench and rushed through the field. Glechik could not let him desert. He fired. Now he alone had to end the battle.

Glechik was no longer afraid. In his mind, "the absolute insignificance of all his past, it seemed, such burning, insults appeared". "Something new and courageous" entered the soul of a previously timid boy. Suddenly he heard "surprisingly dreary sounds" full of almost human despair. It was a crane wedge flying south, and behind it, desperately trying to catch up with the flock, a lone crane was flying and screaming plaintively. Glechik realized that he could no longer catch up with the flock. In Vasilka’s soul, the images of people whom he once knew “grew and expanded”. Captured by memories, he did not immediately hear the distant hum of tanks. Glechik grabbed a single grenade and waited, and in his soul, seized with a thirst for life, a crane shouted.